David Stern spoke at my university recently. He explained that one of the central functions of the Passover Seder and the Haggadah, the prayer book associated with that ritual meal, is to collapse chronological time for the participants and thereby to empower them to engage in a particular mode of Jewish imagination. Stern focused in his talk on the particular tradition of illustrating Haggadot and he tantalized his audience, composed primarily of members of the St. Louis Jewish community, with illustrations spanning nearly 800 years of history. Why, Stern asked, did generation after generation of Jews invest so much time and money into illustrating their Haggadot, when they did not treat other religious texts similarly?

To answer his own question, Stern referred to one of the Haggadah’s central texts, a gloss on the Mishnah, the ancient Jewish law code which contributed most of the Haggadah’s core content:

“In every generation a person is obligated to look upon himself as though s/he went out of Egypt, as it is said ‘And you shall tell your son (child?) on that day, “It is because of what the Lord did for me when I went free from Egypt (Exodus 13:8)”’”

We then looked at further illustrations – in a new light. Each drawing or carving projected images of contemporary Jewish life and tribulation back upon the Exodus myth of slavery and redemption. Medieval Spanish Jews dressed the ancient Hebrews in Iberian garb. The Survivor’s Haggadah,published by the U.S. Army in 1946, depicted slavery as internment in Auschwitz. For centuries, this is how Jews have understood their collective place in the universe. They experienced the entirety of human and divine history as culminating in the Passover meal as celebrated in the present moment – a move which colored the past with the cultures, concerns, and qualities of the contemporary.

Stern’s talk excited me, but it left me wondering about postwar Jewry. After all, the last Haggadah that he referenced dated from 1946. What about us?

Let’s set aside the Maxwell-House Haggadah, which for decades was among the most commonly used in the USA. The company has sold over 50 million copies to date (footnote 1). To my mind, that only proves that Maxwell House took an interest in Jewish consumers and that Jewish consumers took similar interest in conspicuous American consumption – and perhaps less interest in the quality of their Haggadot.

Yet late-twentieth-century American Jewry did produce important Haggadot, including The Freedom Haggadah for Soviet Jewry. During the 1970s and 1980s, American-Jewish leaders imbued their campaign to “free” Soviet Jewry with new religious meanings and rituals that eventually coalesced around the Passover holiday. At the same time, Jewish families brought the public-political sphere into the private-religious realm, i.e. into their homes, by altering the Passover Seder and their Haggadah in ways that “constructed their [political] efforts as a religious imperative (footnote 2).”

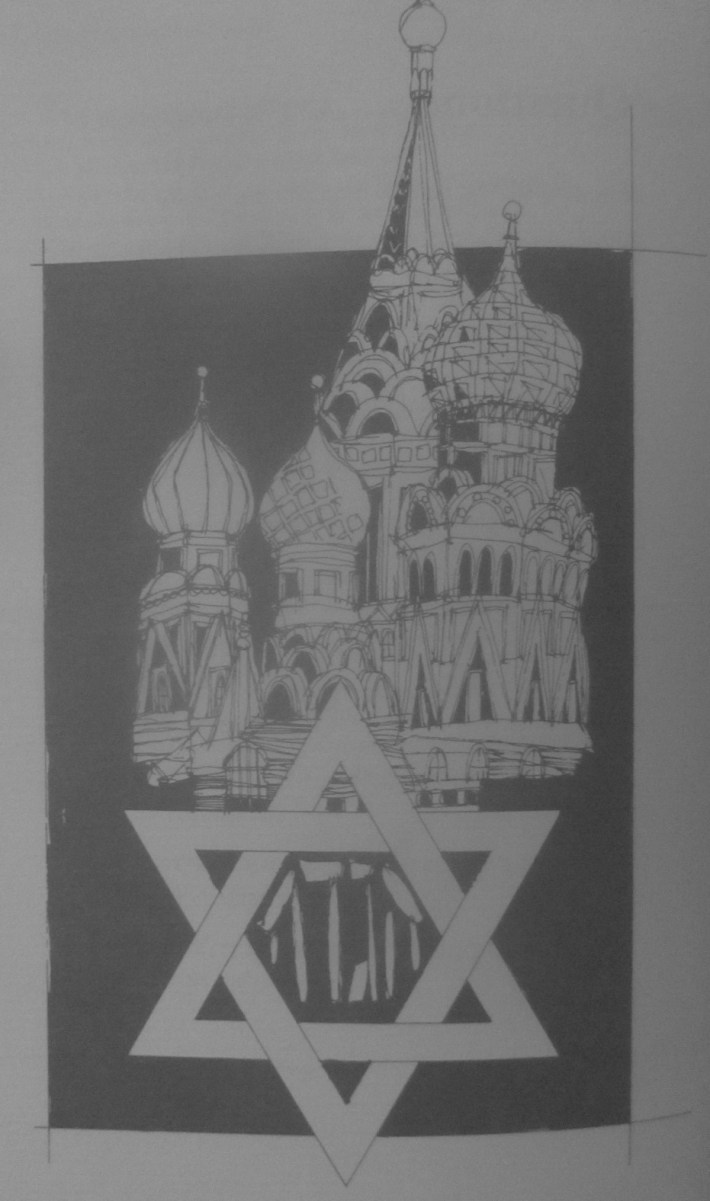

As might be expected given Stern’s talk, the Freedom Haggadah included novel illustrations:

Mark Podwal, 1972 (footnote 4)

Mark Podwal, 1972 (footnote 4)

Though similar to the Haggadot of earlier periods, it also represented a fundamental shift in Jewish imagination. Time still collapses, to be sure, but the bearers and readers of the Haggadah are no longer included amongst those who need redemption – amongst those pictured in the Haggadah and projected back upon history. Rather, American Jews overlaid the Israelite struggle with images of contemporary Soviet Jewry. This implies that they understood themselves to have been – at least partially – redeemed and liberated, living the good life in democratic-capitalist and Zionist America, with access to Israel.

Indeed, they may not have been the first generation of Jews to feel this way. Professor Stern showed us modernist illustrations from an interwar German Haggadah, the aesthetics of which – in my opinion – offered testimony to a strong feeling among German Jews that they had been fully integrated into German society and culture. It evoked comfort in the present moment, rather than suffering, slavery, and exile therein.

What happened next? Where are we today?

The Soviet Union collapsed and one-million Soviet Jews immigrated to Israel between 1989 and 2003 (Footnote 4). Shaul Kelner writes,

Within a decade of the movement’s end, observers of American Jewish life were already speaking of a populace less inclined to locate meaning in the politics of redemption, and of a communal leadership focused not on unity in the face of external threats but on factional conflicts and fears of dissolution from within (footnote 5).

There are still plenty of creative Haggadot, with roots in the same period – and politics – as the Freedom Haggadah. During those same decades and still today, American Jews composed and continue to publish Haggadot for Jewish feminists, the LGBTQ community, alcoholics, and others. These reflect, in the words of Deborah Dash Moore,

… the growth of liberation movements… that emphasized a kind of narcissistic individualism [that] threatened the very concept of communal responsibility uniting Jews throughout the world (footnote 6)…

To be clear, I support these movements and don’t understand this trend exactly as Moore describes it. (And, even if I did, perhaps “individualist” would have been a better turn of phrase than “narcissist,” with all of its negative connotations.) [Note: I am better acquainted now with Moore’s work and have realized that we likely share more in terms of perspective than I understood at the time that I wrote this. JL, 2020.] Responsible community construction can never be completed if it is achieved at the expense or exclusion of community members. Moreover, the experiences of alienated individuals and groups can be used to create more inclusive and meaningful narratives and practices for the entire community of which they are and should be a part. Moreover, many find tremendous strength in these reconceived rituals. They enrich us all, regardless of our subject positions. (To be clear, I have no idea how Moore feels about this phenomenon and do not expect that she thinks of it poorly. This is merely a statement of my own perspective.)

Other new Haggadot address more universalist concerns, like global hunger and the environment, or focus on particular political issues like the Israeli-Palestinian conflict or Darfur. (See the Reform Movement’s Religious Action Committee for downloads.)

What is missing, however, is the projection upon the ancient past of a totalizing, yet locally focused, picture of contemporary Jewry. (In other words, what is missing is the imagination, not only of the Jewish past, but also the Jewish present in terms of a specific community, its concerns, and its needs.) The process started during the Cold War, when American Jews imagined themselves to have been already redeemed and thus responsible for the liberation of other Jews. Now that Soviet Jewry no longer occupies our minds, we seem to have lost our ability to collapse time and, with it, an important part of our historical imagination.

This brings me to the last set of Haggadot that I will address. Contemporary authors have blessed us – literally and figuratively – in recent decades with scholarly Haggadot that draw upon centuries of texts and traditions. We might call them “historiographical Haggadot.” (See the Schechter Haggadah for an example of excellence in this regard.) They contain pictures and commentary from an array of sources that teach us about how other Jews in other places and at other times projected themselves upon the Passover story. It is as if they ask their reader to

look upon himself as though he were a Jew of another era looking upon himself “as though he went out of Egypt.”

These Haggadot call upon us to tour through the Jewish historical experience, to take upon ourselves the guise of Tevyeh the Milkman or Don Isaac Abravanel, but they do not call us by name, nor do they ask us to identify ourselves. This brings to mind the warning issued by Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi in the conclusion to his revolutionary work, Zakhor: Jewish History and Jewish Memory:

The decline of Jewish collective memory in modern times is only a symptom of the unraveling of that common network of belief and praxis through whose mechanisms, some of which we have examined, the past was once made present. Therein lies the root of the malady. Ultimately Jewish memory cannot be “healed” unless the group itself finds healing, unless its wholeness is restored or rejuvenated. But for the wounds inflicted upon Jewish life by the disintegrative blows of the last two hundred years the historian seems at best a pathologist, hardly a physician (footnote 7).

Unfortunately for you, who have indulged me thus far, I am only an apprentice historian – a junior pathologist of memory at best.

Personally, I embrace this historiographical and “narcissistic” turn. I welcome it as an invitation to play seriously and self-critically with tradition – and to find within it pluralities and modalities that resonate, if only fleetingly, with the concerns of the day. Rather than collapsing all of Jewish history and transcending time by casting it in our own image, we unfold ourselves across two millennia of Jewish historical imagination. And we claim with this move the right to invest our activism with holiness – however conceived – and the strength to fight our personal struggles in the company of fellows both present and long vanished.

To those who fear that this a transition of Jewish historical memory threatens to undermine Jewish “peoplehood,” I first remind you that I am merely a junior pathologist of history. I can offer no remedy to stop the flow of time nor wrest our communities from the gravity of broader cultural processes. I hope, though, to offer you solace and perspective.

I perceive tremendous potential in our new historical practices for momentarily experiencing the tribal – for “seiz[ing] hold of a memory as it flashed up at a moment of danger (footnote 8)” and bending it towards ourselves. We can celebrate our communion in time and tremble together at our shared concerns for the future – in moments of prolonged intentionality. Yet we can also choose to travel lightly through these practices of peoplehood, without attributing to them political imperatives – without succumbing to the temptation to perceive ourselves as a chosen singularity at the expense of (or worse, set against) “others,” both internal and external.

I admit that this is a difficult challenge, even for those among us who embrace it. And we don’t understand ourselves fully yet. We are a hyperlinked generation – each of us with our own unique and ever-changing arrays of connections across history, communities, genders, and religions. Managing such selves and the communities we create with them requires hard work, dedication, and education. But just try to take from us our networking devices! Tevyeh will not find a comfortable place in our midst and in our time. Yet evolution does not happen because things stay the same. The brave bearers of today’s mutation will survive to lead longer and fuller lives in a more interesting tomorrow.

And so, I turn to you. How will you “see yourself” this year “as though you went out of Egypt?” Will you be in the company of the Jewish people? Or will you find redemption and freedom alongside a different cohort (or sub-set) of people, with all of humanity, or with the environment?

Chag sameah.

Footnotes:

1) http://www.nytimes.com/2011/04/09/nyregion/09haggadah.html?_r=0

2) Shaul Kelner, “Ritualized Protest and Redemptive Politics: Cultural Consequences of the American Mobilization to Free Soviet Jewry,” Jewish Social Studies: History, Culture, Society, n.s. 14, no. 3 (Súring/Summer 2008): 11.

3) http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/Immigration/immigration.html

4) Let My People Go Haggada, 1972.

5) Kelner, 30.

6) Deborah Dash Moore, B’Nai B’rith and the Challenge of Ethnic Leadership (NY: SUNY Press, 1981), 249.

7) Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi, Zakhor: Jewish Memory and Jewish History (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1982), 94.

8) Walter Benjamin, “On the Concept of History,” http://www.sfu.ca/~andrewf/CONCEPT2.html

Here here!

My illustration should not be credited from “The Freedom Haggadah” since I recall there were problems concerning my permission to CLAL for use of my art. The credit should be from my “Let My People Go: A Haggadah” (1972) in which the art was originally published.

Dear Mark,

I tried to send this once and I do not know if I succeeded. I apologize for any inconvenience or discomfort that my post has caused. Initially, I thought that including a properly cited picture of your illustration fell within my rights as per the academic “fair use” exception. Was I stretching that category? If you like, I would happily take the photo down and replace it with a description. Alternatively, as you suggest, I would prefer to fix the citation. I leave it to you. You were so kind to me when we met in your office in NYC. I would hate to offend you. Please let me know what you would like me to do.

I hope that you are well.

Kind regards,

Jacob